Authors of Tapestry in Bronze

1 When and how did you first encounter the Greek myths? Was it at school?

When I was six my grandfather gave me a book on Greek mythology. The book was aimed at kids, with simple language and lots of illustrations. Funnily enough my grandfather’s first name was Homer. He hated the name – he made everyone call him “Duke” – but I like the fact that I come from the line of Homer.

2 When did you decide to write a series of novels based on the myths?

When I was 14 and a freshman in high school, we read Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. I felt then that the story would be more interesting from Jocasta’s point of view, but I was sensible enough to realize that I did not have the skill or the knowledge to write it. The idea stayed with me, and I finally reached a point where I felt ready to attempt it, in collaboration with Alice Underwood.

While we were writing we researched who had been in charge of Thebes before Laius came to power. The queen was Niobe, the one whose children, according to the myths, were killed by the arrows of Apollo and Artemis. Obviously the gods did not really kill the children! When we examined many myths simultaneously, we believed we discovered the actual murderer. That was one reason for our decision to write the Niobe trilogy: Children of Tantalus, The Road to Thebes and Arrows of Artemis; we wanted to expose the actual murderer. We were also fascinated by the people in the stories, for they are still influencing us today.

Guardians of Thebes

3 You write in partnership with Alice Underwood. How did that come about?

We were colleagues who had collaborated very successfully on other projects. We discovered we both had an interest in creative writing, and especially in Greek mythology. We had tied for first place in a little short story writing contest, which seemed to be another encouraging omen.

4 How does that work? Do you do a chapter each, or do you work together? Are you in the same room, or is it all done by e-mail?

We often meet in at the beginning or the end of a book while we figure out the timeline and other major issues. If we’re in a busy time in the writing process, we’ll usually have a long phone call on weekends. And there are thousands of emails. Alice has 8 different folders in my Outlook: one for each book, one for general writing project emails, and another for other stuff.

It took us a while to figure out how to best use our writing strengths and weaknesses which are fortunately complementary. I am very good at plot so I usually do the first draft. Alice is better at visual details so she adds most of the description afterwards. The process is iterative: she suggests some plot details and I even do some description. She also does all the covers, so if you’re admiring the covers, doff your hat to her.

5 What made you decide to focus on the Theban stories, rather than any of the other myths?

My initial fascination was with the story of Jocasta, and as that was set in Thebes, it led naturally to the other stories in Thebes. Our current project, based on Clytemnestra, has little do with Thebes.

6 How many books are there in the series? Is it complete?

We planned six novels and have written five of them. The novels are Jocasta: The Mother-Wife of Oedipus, and its direct sequel, Antigone & Creon: Guardians of Thebes. There’s also the Niobe trilogy: Children of Tantalus: Niobe & Pelops; The Road to Thebes: Niobe & Amphion; and Arrows of Artemis: Niobe & Chloris.

7 You have obviously researched the period and the background very carefully. What were your main sources?

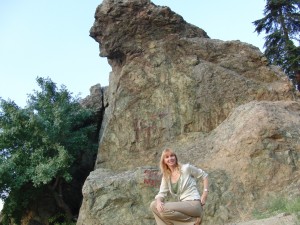

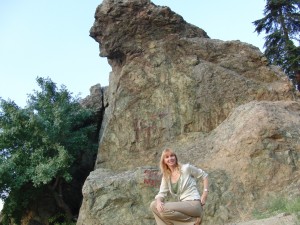

We have both visited the places involved. I spent a day with the archaeological director at Thebes, and he drove me around to some of the important sites in the area. I have also explored the ruins at Delphi, Pisa/Olympia, Argos, Tiryns and Mycenae. I went to Turkey, to visit the Niobe rock, as well as the statue allegedly carved by one of her brothers. Then there are the many museums in cities such as Thebes, Athens, Olympia, Rome, Jordan, Turkey, London, Berlin, Munich, Paris and New York. Besides that, we have watched documentaries, read books, and corresponded with the owners of several websites dedicated to Greek mythology. There’s a bibliography and a set of links at our website.

8 Do you think the original myths have any historical truth, or are they just folk tales?

We think that many of the men and women did exist. Fantastical elements such as centaurs and winged horses did not, but places such as Troy have been located as well as others. Just outside of Thebes are a pair caves which have been determined to be royal tombs. Legend says that they are the tombs of Eteokles and Polynikes, the twin sons of Oedipus and Jocasta. In Thebes there is still a fountain named after Dirke. Why was the Peloponnesus given that name if Pelops never existed?

However, in some of the myths, and not just the fantastical portions, there are contradictions and inconsistencies. For example, after the war between the sons of Oedipus at Thebes, what happened to the daughters? In the most famous version Antigone kills herself but that contradicts other stories about her. We research the different versions and choose carefully between them.

9 If they are just folk tales, why do you think they were made up?

They were made up for the same reasons that people make up stories today: for power, glory and entertainment. Someone trying to strengthen his claim to a throne improved his credibility by saying he was descended from a god. In some cases we even know who the real father was, and yet the hero still made the claim. Herakles’ real father was Amphitryon, not Zeus.

We have a better-attested example in later history, when Alexander’s mother decided that her son’s real father was Zeus, and not Philipp. She was trying to improve her son’s claims to glory. Then there are all the times that the Roman senate voted to deify various Caesars.

Other stories seem to be a combination of glory-seeking and entertainment, such as the fights with beasts and monsters. We believe that bards frequently stole from other bards, so that if someone had a good bit about a hero fighting a giant in one song, another bard might copy it into his song to glorify his own hero.

10 You have succeeded in taking the more incredible events in the stories, for example the sacrifice of Pelops to Zeus by his father and his subsequent return to life, and giving them a believable explanation. Was it difficult to see what might lie behind the myth?

We work very hard at providing natural explanations for the events which seem supernatural. We don’t believe in supernatural events and we don’t see why readers today would do so either. So when Tantalus offers his son Pelops as a meal to the gods, we had two major challenges: how to explain his return to life, and how to show the gods’ arrival. As resurrection falls into the category that we consider supernatural, Pelops does not actually die in Children of Tantalus, but is simply very close to it. How to have the gods show up was difficult, until I remembered having witnessed a meteor shower that was as spectacular as fireworks. A sight like that might have made the people of three millennia ago believe that the gods were descending from the heavens. We timed the banquet of Tantalus to coincide with the Leonid meteor shower that takes places every November. Of course the characters don’t know that it’s a meteor shower; they believe that the gods are on their way, but hopefully readers see both sides.

Coming up with these explanations is a challenge, however, and so we have hesitated to attempt some of the other stories. Herakles is fascinating – we met him in Antigone & Creon, for his first wife was Megara, one of the daughters of Creon – but we don’t know how to depict all the monsters in his labours. They’re just too fantastic.

11 Roughly when are your books set, for example in relation to the Trojan War?

Our current project, based on Clytemnestra, Agamemnon’s wife and killer, is contemporaneous with the Trojan War. The other stories are set one or more generations before. We have a huge spreadsheet for tracking events and characters to make sure that our novels don’t contradict each other. The characters in one book, however, may interpret the events of another novel differently.

12 I see there are Greek versions of the books. Do you speak and write Greek or did you have them translated?

Unfortunately we do not speak Greek. We read the alphabet well enough to drive around the country and to sound out place names. Kedros, our publisher in Athens, arranged for and paid for the translations.

13 I notice that your books are published by Create Space, which is a self-publishing facility. Did you offer them to mainstream publishers? If so, what was their reaction?

Yes, we had an agent who repeatedly tried to market the books and nearly succeeded with big names such as Penguin and Random House. The problem with Greek-mythology-based books is that they have an oft-deserved reputation for being difficult and inaccessible. We have worked hard to overcome this in our own writing – and it is a real challenge – so much so that when we get people to pick up the novels they find that they are far more engrossing and accessible than they expected.

14 What plans do you have for future books?

We have written five of the six books that were in our original set. We’re currently working on the story of Clytemnestra. We may write more together, but we have not settled on which ones.

In the meantime, I’m also writing some mysteries. I had an idea based on Jane Austen’s Emma and so I wrote The Highbury Murders: A Mystery Set in the Village of Jane Austen’s Emma. I had so much fun with it and the response has been so positive that I am working on other cosy mysteries, although in a modern setting.